One day back in nineteen ninety something while I was suffering from an acute case of being fourteen years old, my mother dragged me kicking and screaming (more actually pouting and moaning) to Brighton, UK, where we walked along the beach and through its famous Lanes.

Brighton, UK

Photo by Dominic Alves

One of Brighton’s Lanes

Photo by John Starnes

Even from beneath the ominous black cloud of teen angst, I couldn’t help but notice that omfg this place is so awesome, not that I was about to let on to anybody, least of all my mother. While we were walking through a part of the lanes that had sprouted a ceiling, making it suddenly more like an indoor-outdoor shopping mall, a school kid approached us with a video camera and told us he was doing a project for one of his classes. I felt begrudgingly compelled by social propriety to interact with the young lad as he asked me what I thought about the “world cup”. At fourteen, I had no idea what a “world cup” was, but I supposed from his enthusiasm that it was probably pretty good, so I said something vaguely positive and then finally confessed I had no idea what he was talking about. At this point, he somehow figured out that I was from the good ol’ U-S-of-A and yelled out “Jackpot!” right into the echo chamber, much to my dismay. Then he went on to enjoy immensely the process of teasing out the extent of my ignorance, archiving every detail of my humiliation for posterity.

That story really doesn’t have much to do with anything apart from being the first time in my memory that I experienced a car-free zone, and despite my best efforts to remain grumpy about it, Brighton’s Lanes made a lasting positive impression on me that day. Altogether, my mother spent two weeks of her life ferrying me and my frown around England, and by the time I arrived back home in Minneapolis, everything in my home town appeared to be unnecessarily large and spread needlessly far apart. I immediately felt smug and cultured, smarter and more experienced than my fellow countrypeople, which suited my chosen teenage persona just fine.

Several years later, long after I’d allowed smiling back into my life, I discovered this little corner of Boston and fell immediately in love, this time openly affirming my adoration to my travel companion and wondering aloud what it might be like to live above a shop in one of these tiny lanes.

Small pedestrian zone in Boston

Photo by Margaret Napier

A few years after that, I moved to London, where I worked within walking distance of Neal’s Yard and lived within weekending distance of all manner of densely populated, car-free or car-light, commercially and culturally rich neighborhoods in continental Europe.

Amsterdam

Photo by Moyan Brenn

Prague

Photo by Moyan Brenn

Lyon and Berlin

Photos by Ioan Sameli and Ana Rey

The more of these places I saw, the better I was able to articulate my idea of urban utopia.

I used to be pretty sure my ideas were unique in all the world when I’d tell others that the best cities of the future will be those in which private cars are nowhere to be found and all of the amenities you might find in Manhattan, Paris, or London are just outside your doorstep or a short walk, bike ride, rickshaw ride, or streetcar trip away. It’s an image reminiscent of the fortified cities of ancient times, in which the walls are replaced by parking garages for those who still want to own cars for trips outside the city. I’d learn later that a few cities which more or less fit this description already exist, but I was not wrong that this sort of urbanist’s neverneverland is nowhere to be found in North America.

Mmmm… Venice

Photo by Tambako the Jaguar

Since moving to San Francisco eight years ago, I’ve gotten used to meeting other urbanists who have dreamt up the very same narrative for our blissfully car-light future, so I was recently unsurprised but still intrigued to discover Tracy Gayton and the Piscataquis Village Project.

Piss Caticus

Piscataquis (“Pisk Att-icus” or “Piss Cat-icus”) Village is an as yet non-existant car-free rural town full of narrow lanes lined with arcades and attached row houses, punctuated by small plazas and internal courtyards. Many of the row houses contain commerce on the ground floor and, though this is not specifically called out in any of the official documents I’ve yet reviewed, I think I can say with confidence that these commercial enterprises feature large windows to light up the streets at night, and patios with seating spilling out into the narrow lanes, bringing about a community feel and the sort of safety, charm, and photo opportunities we usually feel we have to fly overseas to experience.

Piscataquis Village still only exists in Tracy’s mind and in the minds of a few dozen “contingent investors”, but at least Piscatiaquis Village has a name, a website, a reputation, and the beginnings of a potential future citizenry, which is a lot more than I can say for the ideas I’ve gone on about at length over pitchers of beer with my urbanist friends.

Tracy has decided to locate the whole thing very far away from any urban center, in what is now an extremely sparsely populated rural area in Middle Maine, where zoning laws, bureaucratic hurdles, and NIMBYistic resistance are all likely to be absent or minimal, allowing the march of progress to move forward relatively unimpeded.

As delicious and tempting as this project sounds to someone like me, the project will almost definitely ultimately fail to recruit me for a couple of reasons:

1. I’d Need a Car

The first and most obvious downfall of the plans as they are currently being presented is that there is, as of yet, nothing in them about establishing any kind of regional public transit to anywhere at all. This means that in order to get to and from the village, which is by its own admission in the middle of nowhere, I would either need to buy a car, arrange to use someone else’s, or hitch a ride with someone else whenever I want to leave the 500 acre lot.

Even if I was down with the idea of purchasing a car in order to drive back and forth from my car-free utopia, I really can’t ignore the fact that after a decade of never driving a car, I am frightfully and inescapably bad at it and should by no means be allowed anywhere near the driver’s seat of any highway-legal motorized vehicle whatsoever, and I certainly should never be permitted to drive any such thing on roads or anywhere else, no matter what my California driver’s license declares me capable of doing. I’ll tell you what, California doesn’t have the first clue who can or should be driving a car. I have a permanently disabled ankle and a freshly rotated pelvis to show for California’s ridiculously relaxed approach to handing out driving licenses to anybody and anything. If California refuses to police me, then I must police myself and steer clear, so to speak.

It seems to me to be a bold move on the part of the Piscataquis Village Project to dismiss out of hand as potential future citizens of their car-free utopia all of the people in the world who are already living a car-free life and have no interest in ever driving a car or otherwise being dependent on one. No, no, if I can’t hop on a train or a bus and be at the nearest international airport in under an hour, all bets are off for this card-carrying member of the car-free choir.

2. There’s a Total Creepy Fake Town Potentiality

If Pisk Atticus comes into being, there is reason to believe it may not mature past being a ghost town or a remote commuter village that brings lots and lots of car traffic into the neighboring job centers.

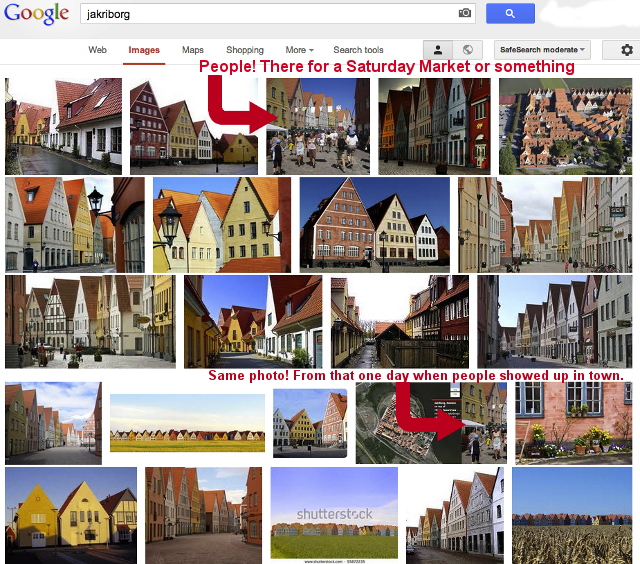

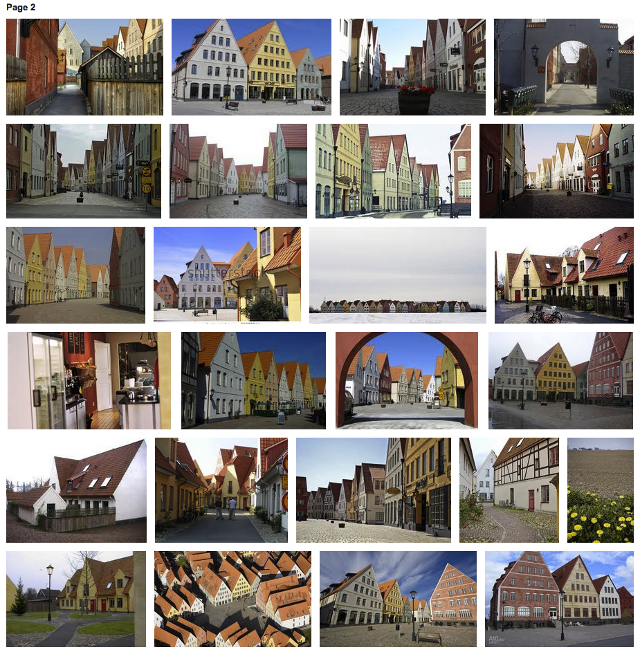

Jakriborg, a similar intentional car-free community recently established in Sweden, suffers from a “Creepy Fake Town” reputation, and anybody who does a Google Image search about Jakriborg can immediately tell you why.

Wait. Where are the people?

Even more no people!

Even though Jakriborg is on a well traveled train line between two very nearby population centers and over 500 families currently live there, and more people are moving there every day, from a Google Image search point of view, it looks conspicuously empty for all the density of its built environment. I’d guess that’s because, while it looks like it’s trying so hard to be so much more, it is still mostly functioning as a suburb. Because of its location and connectedness, I have hope that Jakriborg will one day grow into its britches and become a destination for jobs, commerce, and culture, but until it does, it’s going to continue to look more like a housing development than a town.

There is quite a lot less in Mr. Gayton’s plans to comfort me that Piscataquis Village will mature beyond being a peculiarly organized suburb, retirement community or, worse, a collection of summer homes. Some of the investors who are called out as examples in one of the project’s own slide presentations openly confess they are either planning to use their lot as a vacation home or are possibly going to leave it completely uninhabited, maybe even unbuilt. Some say they want to retire there, which is better than merely vacationing there, but is anybody planning to move in and open a shop? Employ people? Take a job in town? Who will shop at the shops if people are only using the village as a vacation home or to store their empty lot indefinitely?

I can’t help but suspect that there’s not enough in the plans yet to attract the economic and cultural forces it needs to overcome these pitfalls, and the density of the built environment will only contribute to the feeling that those who do live there are to be revered as the survivors of a neutron bomb event or perhaps not survivors but ghosts.

OK, so now what?

So where will our future utopian car-free village come from? Mr. Gayton is after all completely correct in pointing out the infuriatingly uphill battle in our existing cities against NIMBYism and outdated, myopic, and inhuman laws and engineering codes keeping the car-saturated status quo alive and killing in every single corner of every last American city.

Mr. Gayton points to the failure of the Gaslight Village Project, an attempt to build a car free utopia from scratch in a neglected part of Philadelphia, as further evidence we should give up on changing our existing cities and focus instead on going back to the land and building there.

However, if you look around these days, there are reasons for renewed optimism that the tide is turning for our cities generally and in San Francisco particularly:

- In recent years, cars have started going out of style. Today’s tweens care more about their iPod Touches than they do about spending a bunch of time and money just to relieve their parents of their chauffeur duties.

- And these are the people who will be inheriting our urban cores.

- Which, by the way, are steadily vacuuming up the population around them like hungry hippos, making our cities increasingly dense.

It’s people. They’re making our cities out of people!

Photo by Andrew Shell - To cope with the projected density, San Francisco has long been working on overhauling its bureaucratic processes and funding mechanisms to expedite bike, pedestrian, and transit improvements, and despite recent setbacks, we are still more or less on track.

- And we can expect less resistance from local businesses as studies from more and more cities, including New York, Portland, and San Francisco, demonstrate what urbanists have known for years: that trading car space for bike, transit, and pedestrian space is good for business.

So instead of abandoning our cities, maybe we should take another look at why projects like Gaslight Village failed. For example, instead of eyeing the empty or neglected neighborhoods, perhaps we should examine the possibilities in the parts of our cities which already have a lot of the key characteristics of the promised land: density, public transport, mixed uses, a large pre-existing car-free constituency, and obvious long-standing cultural and economic connections. With so many of these things already in place, the remaining bureaucratic, political, practical, and social hurdles to filtering out most of the cars and replacing them with more practical alternatives may very well end up being beans in comparison to the complexities of setting up a brand new car-free urban center anywhere else.

In my mind, the only question, really, is which city will crack this nut first, and while I see stiff competition out there, I’m still rooting for San Francisco, and I think we have a good shot at the prize. In particular, I think Chinatown, already the densest neighborhood this side of Manhattan, holds a lot of potential to be our toe-hold on a future car-free utopia that you’ll be able to get to and from on foot, on BART, or on the MUNI F, J, K, L, M, N, T, 1, 2, 3, 8X, 10, 12, 30, 38, 41, 45, or 76.

I’ll explore this idea further in another post.