So here’s a thing I’ve been failing to mention for over four months now: I don’t live in San Francisco anymore. That’s right, folks, you heard it here last. But if you didn’t see that coming, you’re not paying attention.

Even though I lived in San Francisco for over eight years, I never could quite identify as a San Franciscan. A major reason for this is that I biked daily on the roads there, more often in SOMA (where I worked) than in any other neighborhood, and there are few things that will make you feel your place as an outsider and an intruder in San Francisco more than riding a bike every day in SOMA.

Wait. But San Francisco has such a strong bicycle culture, right? How could I possibly feel like an outsider as a cyclist in San Francisco?

Oh good! I am so glad you asked that acutely irritating question. What a convenient lead-in for me to talk about bike culture.

Nutritive vs Selective Bike Culture

I think about bike cultures the same way I think about bacterial cultures: There are nutritive bike cultures and then there are selective bike cultures. In Copenhagen and in most cities in the Netherlands, you find the nutritive kind of bike culture, where people of every age, ability, and socioeconomic status can and do use bikes daily to safely transport themselves and their stuff from wherever they happen to be to wherever they happen to be going, at any time of the day or night and in almost any weather. This is a pervasive, heterogeneous bike culture on a regional level that completely overwhelms the kind of selective, homogeneous, minority bike culture that thrives in San Francisco and to varying degrees in other U.S. cities.

[youtube width=”635″]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_-y_26lgm9I[/youtube]Groningen has a nutritive bike culture. You can tell because 57% of all trips are made by bike (contrasted with 3.5% in SF) and helmets are nowhere to be seen because biking here is safe.

A nutritive cycling environment is one in which many different types of cyclists thrive. In obvious contrast to the nutritive environments found in Dutch cities, in the much more selective San Francisco you find the following considerably harsher conditions:

- A lack of safe infrastructure for people who bike.

- A lack of support from law enforcement for people who bike.

- A lack of support from law makers for people who bike.

- A lack of education for people who drive about how to operate their cars safely around people who are operating bikes.

- A compliant media to keep drivers misinformed and dangerously agitated against people who bike.

All of these factors serve as the “selective media”, combining to give you San Francisco-style “bike culture”, which is really a bike sub-culture: A minority of people who, despite all of this, actually still bike to commute. Having been carefully selected by their inhospitable environment, they tend, on the whole, to be somewhat similar to one another. They’re the young, able-bodied, likely childless, “bold and fearless” 3.5% or so who are not convinced by points 1 through 5 above to actually abandon their bikes.

[youtube width=”635″]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4LvTpg0VMrM[/youtube]San Francisco’s selective bike culture. Encounter another cyclist at a red light? Get his number. He might be your soulmate.

So in San Francisco, not only do bike commuters as a group hold a lot more in common than bike commuters in Amsterdam or Copenhagen, they also have a whole lot of sticky stuff to bond over. In San Francisco, when cyclists get together, they share stories about terrifying close calls with cars[1], often involving drivers who are talking on their phones, texting, or getting their morning nap in over a hot coffee and a newspaper. People share tales of broken collar bones, of getting “doored” on their way to work, of various experiences with the police department’s anti-cyclist bias, or of being passed too closely, “right-hooked”, pressured off the road, or screamed at, honked at, or worse, merely for taking their legal place on the road. And once you have a few stories of your own to share, you inevitably started to feel a bond and a sense of belonging with this bunch of people who call themselves city cyclists. But you can find this in any bike-unfriendly city which has an appreciable number of people who bike. If you look hard enough.

To illustrate the difference another way, imagine two people have just arrived at a book signing. Both got there on bikes and are parking them outside just a few paces from each other. If this story were set in Groningen, our narrative would end there. The two would almost certainly fail to register each other’s existence, especially through the crowd of other people parking their bikes in the space between them. If we set it in San Francisco, however, if these two people didn’t already know each other, they would quite likely notice each other as the only two people locking bikes up to adjacent parking meters, and they’d also be more likely to be close in age and temperament. They would probably smile at each other as they walked toward the door, and soon they’d share a knowing eye-roll, as the host, astutely spotting one of their helmets, asks if they arrived on bikes and goes on to comment that it’s “a nice day for a bike ride”. They would use the bicycle as an icebreaker during mingling, and they might later exchange numbers, go on bike dates, and perhaps one day move in together, have children, enroll their kids in a bicycle safety class from the earliest possible age, sign them up to be bicycle valet parking volunteers at community events, and ultimately go to their 20-year SFBC member party together. Or perhaps they would buy cars and move to Danville to keep from having to watch their precious little ones experience the same dangers and police indifference on San Francisco’s streets that they have learned to endure on a daily basis. After all, with young people moving into the city every year, there has to be some attrition to keep that mode-share to a tidy 3.5%.

How San Francisco forged my identity as a “cyclist”

In late 2004, having moved back to the U.S. after living for a couple of years in London, I came to San Francisco on one of those waves of young people moving into the city. I was 28, and I had absolutely no view of myself as a “cyclist”. I owned a department store bike that I had recently bought and enthusiastically decorated for Burning Man. It was heavy, low on gears, full of shock absorbers, and totally ill-suited to biking on even the tamest of San Francisco’s hills. But after discovering that MUNI was not as good at getting me around the city as London’s busses had been at getting me around London, I decided to circumvent MUNI’s unreliability by using my bike to get to work on time.

How embarrassing.

Even though I had stripped the bike of everything pink and orange by then, this decision immediately attracted the attention of my cycling friends and co-workers, and they began to offer me bike advice and camaraderie. One co-worker (who is today of course a good friend) even gave me his old bike when he bought a new one, and I found myself learning what a difference it makes on San Francisco’s hills to ride a proper bike with actual gears and other fancy features, like a lighter frame and a rigid seat post. My 3rd bike was again a hand-me-down from a friend who had gotten himself a new bike. That 3rd bike was the first bike I fell in love with. It was a geared-up, nimble, very light mountain bike with no suspension. It was pure joy to ride. And once I saw myself getting better on the hills and eventually even beating the boys to the top? That was it for me. I was hooked. I had never in my life excelled in anything remotely athletic, so crushing hills and leaving boys in the dust was a completely new and exciting experience for this physically graceless, and socially awkward computer nerd.

The same friend who gave me my 3rd bike also told me a story about how an SFPD officer treated him after a car driver pulled out from a small alley and hit him with her car. The police somehow found my friend to be at fault, and so he received no financial help with his injuries. I was a little incredulous at the time, figuring he must have left some detail out of his story that could have explained why the cop found against him, though I couldn’t imagine what it might have been. I soon learned not to be so unbelieving.

And as the years went on, San Francisco continued to forge my identity as a cyclist. I became more or less loosely affiliated with many different groups of cyclists, from cyclocross and mountain bike racers, to road warrior Strava nuts, to bike campers, bike advocates, eco-riders, hipsters, and even a few fixerati thrown in for good measure. I fell in love with long distance riding in particular, as it allowed me to explore territory I used to think was off limits to those of us without cars. I became obsessed for a while with monitoring my improvement on hills using Strava, feeling the occasional validation that only a hard-fought QOM status on a lung-bleeder of a Presidio hill segment can bring to an introverted “non-racer” like me. And the weight loss was of course a happy side-effect of doing this new thing I loved to do. Despite my surprising enthusiasm for the sportier side of cycling, though, I was always primarily a utilitarian cyclist, just someone who was trying to get to where I was going efficiently without a car, which in itself was more than enough, in San Francisco, to tattoo the word “cyclist” onto my heart (and lungs).

The irony of it all

Ironically it’s this very San Francisco-sourced identity as a cyclist that has caused me to decide that I can’t tolerate daily life there anymore. During my many years on the “bike scene” in San Francisco, I met the occasional “ex-cyclist” who had decided the risk of biking in the city was no longer worth the reward. And after being hit by a presumably-drunk hit-and-run driver that fateful night in SOMA, my 3rd time being hit by a car in SOMA, I felt a very strong pull to become an “ex-cyclist” myself. (Especially since, as is the very disturbing and undeniable norm when it comes to bicyclists who are hit by cars, the SFPD didn’t lift a finger to investigate my hit and run.) I stopped riding to appointments which would require me to bike through trouble spots in the city. And with the exception of group rides, in which I would be safer, I stopped most of my recreational riding. Some days, in order to keep from being overcome by PTSD anxiety fumes, I’d leave the bike at home and take the bus everywhere, despite the extra hours it often took to do so. But my schedule usually wouldn’t allow me to indulge my PTSD, and so I would ride right through the stress and anxiety, enduring the close calls and frightfully inattentive, uneducated, and even hostile driver behavior, day after day, until I finally figured out that I had to decide between being a cyclist and being a San Franciscan.

So at the end of March 2013, with a heavy heart, I left the city that had done so much to shape who I am today. Four months later, I miss my friends, I miss my riding buddies, and I miss the ability to drop in on a bunch of rabid techies at the coolest bar in town to hear first hand about all of the fascinating world-shaping technological innovation going on around me. I miss being in the middle of one of the most happening places on earth. But I don’t miss the daily PTSD triggers and feelings of utter personal stagnation I was experiencing during my last 18 months there.

Now and Later

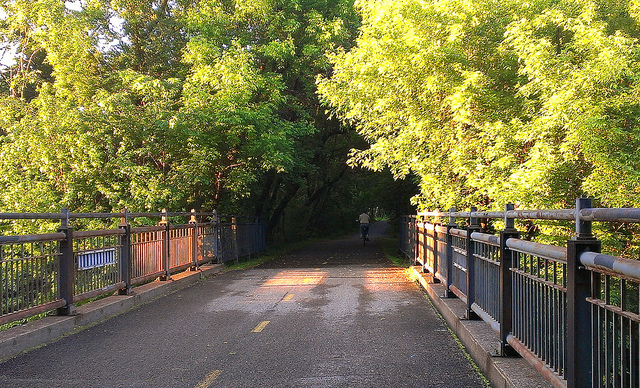

I am currently in a luxuriously dull and uneventful limbo between San Francisco and my next city, in the sensory deprivation tank that is Hugo, MN. Here I have access to my family, my remote job, and a pretty impressive network of completely separated (albeit virtually amenity-free) bike paths to help me keep biking while my body re-learns how to remain calm in the face of the institutionalized injustices and dangers of the American transportation system. But winter is coming, and believe me, nobody wants to be in Hugo, MN when that happens.

Here are just a few (OK, quite a few) examples of the kinds of serenity I’ve been up against here in Minnesota:

Minneapolis’s Minnehaha Parkway Trail, which I got to all the way from Hugo, MN, completely on separated trails.

Minneapolis’s Minnehaha Parkway Trail again.

Lino Lakes Park Trail

Minneapolis’s Cedar Lake Bicycle Highway, which has surprisingly few exits and entrances.

Another Lino Lakes Park Trail…. I know. Ridiculous.

My nieces, enjoying a nameless trail right outside their door. It leads to Hugo’s only grocery store and primary commerce center.

This list would be incomplete without a photo of the famous Gateway Trail.

And finally, my very favorite bike on my very favorite stretch of MN trail.

I will almost inevitably one day reveal here what my next chosen city is, perhaps four months or so after I’ve moved there, or perhaps next week. For now I’ll just tell those of you who don’t already know but may nevertheless think you do: No. It’s not Portland.

[1] In one particularly memorable story, which I heard during my last month in San Francisco, a woman riding southbound on Polk Street somehow ended up momentarily underneath an idling delivery truck together with her bike. She managed against some scary odds to escape without being injured or killed. The driver remained completely unaware of all that had transpired under and around his truck.